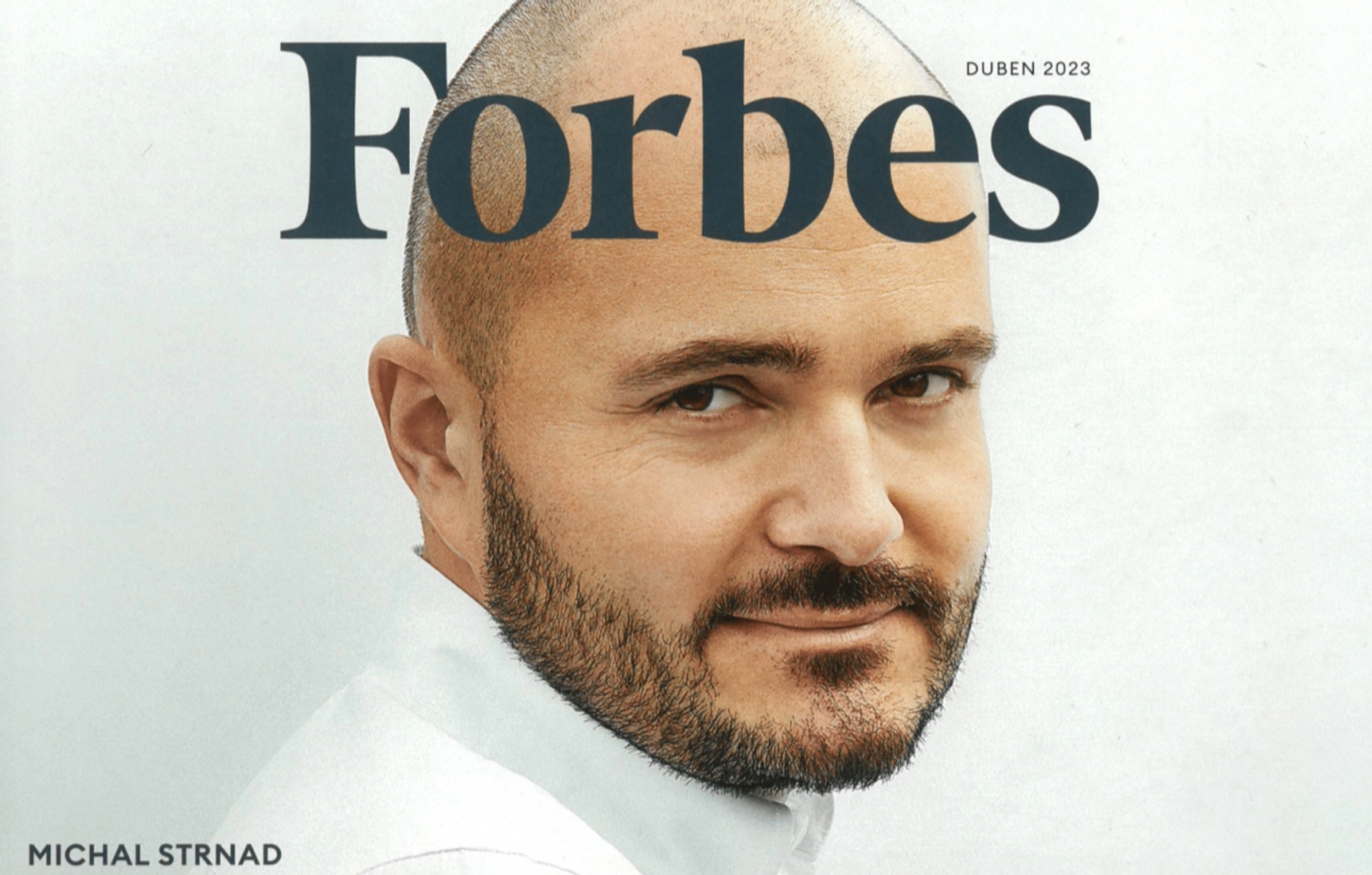

The war in Ukraine has changed everything. Even the view on the arms dealers. The defense industry, as it calls itself, is growing at the fastest rate in the last decade. And together with it the Czechoslovak Group of the thirty-year-old entrepreneur Michal Strnad too. Anyone who wants to look at the weapons business with a skeptical eye should know: nowadays, there are queues at ammunition and weapons factories.

We are publishing the full interview with CSG holding owner Michal Strnad, with the permission of the Czech branch of Forbes magazine, where the text was originally published. You can read it in Czech here.

The extensive grounds of the Tatra Kopřivnice are busy, with finished or unfinished trucks and special military vehicles at every corner; the factory is running at full speed.

"And these are Pandurs for Indonesia," the youngest Czech dollar billionaire and the newest member of the elite global selection of the most successful people in the world shows in the production hall, surrounded by barbed wire and guarded like a barracks, pointing at unfinished and still very raw-looking future armored personnel carriers.

He is thirty and he gets up every morning at five. His name is Michal Strnad and under his leadership, the largest arms-production machine in Central Europe has been operating for ten years. It was once founded by his father Jaroslav as a scrap business and decommissioned military equipment business; today, it has a turnover of almost sixty billion crowns, an operating profit of over seven billion, and orders for sophisticated weapons systems worldwide. And the one, who thinks that Strnad Jr.'s main qualification is the fact that he is the son of founding father, would be very wrong.

Michal Strnad has been leading the entire group since 2013, from the age of twenty-one, initially side by side with his father. Five years ago, he took over the ownership from him and knows every detail of his empire.

He walks past the finished, slightly ominous-looking, mat painted green Tituses and casually turns to the production director of Tatra Defence Vehicle. "Yesterday I spoke with those cable suppliers, they will contact you today," he says decisively.

The production halls of this company are located in the middle of the huge complex of Tatra in Kopřivnice, which also belongs to the Strnad's companies of the Czechoslovak Group. There, a few dozen minutes earlier, he was dealing with late deliveries of gearboxes and engines from the USA.

As we drive past the aircraft maintenance hangar in Mošnov, which belongs to his other company Job Air Technic, he shows which aircraft will be repaired, knows about every order, knows the turnovers and profits of his companies from memory, whether they produce weapons, brakes for locomotives, or Prim watches.

His knowledge about Pandur vehicles for Indonesia will be needed very soon. He will fly to Jakarta. He won't enjoy the exotic islands much – he is going for a quick trip. Sixteen hours there, then a few hours of negotiations, and sixteen hours back. He will deliver 23 Pandur armored personnel carriers here.

"In this business, not only perfect products but also good relationships are essential. And you just have to talk to your customers personally, no matter how many thousands of kilometers away they are," explains the slightly bearded Michal Strnad, dressed in a light dark coat. He spends a lot of time on planes, as well as visiting about forty active companies belonging to the CSG holding.

Under his leadership, the group's turnover has increased tenfold, he is systematically building it in various verticals, and according to Strnad, even better times awaits it. "The arms industry is now completely full, we produce at maximum capacity, we can't have more. And that's how it can be for the next five, ten, or more years," he thinks.

Why do you think so?

It's simple. Just due to the war in Ukraine, ammunition and equipment supplies will have to be replenished that were sent there. Western armies have half-empty warehouses and will want to reach much larger numbers in stock for their own security than before the conflict. At the same time, the security situation has changed, many governments and parliaments have approved much higher defense spending. We already have two percent of GDP for defense in the law, it's just waiting for approval.

What is most needed now in connection with the war in Ukraine? What is the highest demand for?

Artillery and tank ammunition. The production can´t keep up. It could be done, but there is a shortage of gunpowder. It is produced in only three factories in Europe, one of them is the Czech Explosia, although it is smaller. Otherwise, our ammunition factories in Slovakia and Spain are running at full capacity.

Two examples: When we bought an ammunition factory in Granada, it had 35 people and was struggling. Now there are 300 people, they produce ammunition for tanks and guns and they don't know what to do first. The price of tank ammunition has doubled since the outbreak of the war, demand is huge and there is almost a queue.

Are the Czechs in it too?

Yes. The day after the start of the war, we received a call from the Czech Ministry of Defense to secure and reserve capacity for the Czech army. We did that. But no specific order has arrived to this day. When the same and fast demand came from Poland, a clear order followed within 24 hours. But unfortunately, it is delayed with us. We are really running at full speed, this year will be even better in terms of orders and results than 2022.

We may ask stupidly: business is growing because there is trouble in the world…

Today, yes, but we were growing even before the war.

How do you take it when someone tells you: but you make money from selling weapons?

I don't think it's bad, weapons are precise engineering, it's an industry like any other. On the contrary, I think it's a shame that the defense industry has been heavily underinvested in Europe for the last thirty years. Governments did not buy, and we could not invest back into factories.

And today it is all coming back to politicians, and it is hard to listen to. I am not ashamed at all that we are selling weapons. We do not sell weapons primarily for someone to kill or attack with them, but to defend themselves. We are the defense industry, not the offensive.

Yes, even in the columns of statistics, it is called the defense industry. But the perception can be as such, because many people will say that your business has grown dramatically because suffering has increased.

In my opinion, this definition is incorrect. The entire defense industry accelerated and began to be taken seriously after what happened in Ukraine. Because states, led by politicians, finally realized how important the defense industry is.

Would you be upset if someone said you were like Nicolas Cage and Lord of War?

I don't know if I would be upset, I probably wouldn't like it, but I just take it that everyone has a different opinion. I do not take anyone's opinion away. I know what it is like. We are not doing anything wrong, we have more than eleven thousand employees in this field in the group, we provide many people with work, today you could be convinced that we are investing in our companies. We invest in new products.

We’re asking about the morality of this business.

Personally, I don't have a moral problem with it. And if someone has a problem with it, I don't take it away from them, I respect them. And I'm not going to do anything about it. I'm certainly going to keep doing the work that I'm doing and try to be the best at it. At least in the fields where I can.

--

When Jaroslav Strnad transferred the entire Czechoslovak Group to his son Michal at the beginning of 2018, the domestic business circles were full of scepticism. Czech businessmen, together with a part of the public, were convinced that the transfer of assets was only a sham. That Jaroslav Strnad had been damaged by his ties to Russia at the time and had withdrawn from the group, although he retained his influence. When Forbes USA wrote the Strnad story in 2019, it also spoke to representatives of Transparency International. "In our view, Jaroslav remains very active in the holding company and the asset transfer is more of a symbolic gesture," Marek Chromý from Transparency International told US Forbes.

When we talk at length with Michal Strnad, there is absolutely no indication that he is a figurehead. "It's hard for me to prove it this way at the table in front of you, but ask my colleagues who hired them, who interviewed them, who makes business decisions, and how many times they have seen my dad in the company over the last ten years, except when we celebrate birthdays," Michal Strnad shrugs his arms as beef tartare lands on his table at our lunch together. All the time, he seems - for someone in such a sharp business - very calm, sometimes even a little shy. You can see that he doesn't like big gestures or big words, he doesn't behave flamboyantly, and overall, you wouldn't know that he is the youngest Czech billionaire.

You realise how high up he is when he tells you that he bought the private jet we flew to Tatrovka from Radovan Vitek. He has the phone number of the richest Czechs, and he obviously knows most of them well, often in full detail. Of course, we cannot see inside their heads, but there is literally nothing to suggest that Michal Strnad is a set-up, as the market has speculated.

"My son is very young. 25 years old. He is learning. He has been helping me here for a long time. I say, youth forward. But I still want to help him, even though he is doing very well," Jaroslav Strnad assessed it in our interview in 2017. Strnad Sr. himself, who is an apprentice metalworker and has no college degree, says he made his first money from scrap metal. "My first entrepreneurial steps were that I collected scrap metal by hand around the country, cut it up and loaded it for transport to Austria,” Strnad Sr. said at the time.

How old were you when you took the helm of the group? And why so soon?

I was 21. At that time the group was small, comprising Excalibur Army and the logistics company Nika Chrudim, DAKO-CZ producing brakes for rolling stock, plus container production at Karbox. At that time my dad had a manager who ran the group, and he didn't prove himself. We were faced with the decision at that time whether my dad would return to operational management, or I would go there.

Dad didn't want to do it anymore?

Well, I don't know if he didn't, I don't think so. He was still the owner at the time, ownership didn't transfer until 2018. But he didn't want to go back into operations completely, he wanted to do things that he enjoyed, and actually things that he still does today. He does what he enjoys and what he's close to. And so do I, I grew up there.

What do you mean?

Since I was twelve, I've always spent the entire summer vacation, two months, at work. I didn't go anywhere for hobbies, but I worked in the warehouse, in IT, in marketing, in sales, I went through it from a young age. So, I grew up with that, helping my grandmother in the warehouse with the gear, doing everything. When I started running the group, people knew me there and that's probably why I got hired at 21.

You're thirty now. Is it safe to say that the way the group looks today is your creation and your vision?

Yes. If I compare the group in 2013 to 2022, it was something like ten to fifteen percent of what it is today. We have multiplied it tenfold.

Ten years from now?

It will be ten years this year. And if we succeed this year, it'll be a lot more.

And the vision to build a group like this really grabbed you at 21?

It's gradually taking shape. Of course, you're gaining experience and you're also seeing where the trend is going. You're getting to know it more and more and you're starting to have a global overview of the business and its basic pillars. My father in the beginning went after opportunities and he knew how to take advantage of them. We are now building gradually, vertically, a logical group, which today is seventy percent based on the defence industry.

And how does it sound today that you are among the richest people in the world, with assets worth over two billion dollars?

It's nice to hear, but it's not something that's life-changing or something that I'm completely desirous of. It's not the main motivator for why I work the way I do and push it further. It's certainly nice, it's a benefit of all the hard work we've done, not just my work, but also of the team I have around me, and the staff. But it's definitely nice.

Sure, that's not the goal of the business. But how would you explain why you do what you do?

Because I enjoy it and because I want to leave something behind. And we've really built something abnormal. We're already one of the biggest players in the defence industry in Europe. And I think that we, because I'm quite young, can push it more maybe to a global level.

From your point of view, where does your group stand today? Not yet in the top ten European defence companies. Germany's Rheinmetall is, say, three times as big...

For example, Rheinmetall is divided into two parts. Roughly half defence and half automotive. As for defence, I haven't seen their numbers for 2022, but from what I remember they were twice our size. Rheinmetall is definitely someone we'd like to get close to. And preferably surpass it.

Who are the other biggest competitors in the industry?

You must take it on an industry-by-industry basis. It's different in land systems, different in munitions, different in radars. If you look at it from an overall perspective, which is your focus, it's certainly Rheinmetall, Italy's Leonardo, France's Nexter or Thales, but Thales again doesn't do land equipment or munitions at all. We would certainly like to get to the level of these global players. But it must be said that we can beat even these players in tenders today. For example, we have just won a big tender for radars in Indonesia, where we beat both Leonardo and Thales. It is a contract worth almost ten billion crowns.

And what's the secret sauce to being successful in the defence industry and then maybe beating these companies?

This business is very much about relationships. The defence industry is a relatively closed, small group. A small world. And not everybody gets into it, or not many new people get into it anymore. And even those of us who are in it don't really want new people in, that's a logical thing. Anyway, I've been saying for a long time that relationships are more than money. Czechs are generally quite good at building relationships, and setting up a good informal relationship is one part of success. But of course, even good relationships are not enough if you don't have a top product. That's just the foundation. You need to have a good product, global, with potential. You really need to have something to offer to the customer. And then the relationships will help. It doesn't work the other way around. So, the product and everything around it is the foundation.

And maybe a naive question, are relationships built in exactly the same way as in any other business, or does it have its specifics in terms of who the customers are?

It's different in a way that our customers are primarily governments, defence departments, procurement agencies, NATO, traders who buy something from us and resell it on.

Does that exist? Arms wholesaling?

Yes, especially in the US. There are private companies that buy material from you and then resell it to, let’s say, the US state or other customers. Of course, you don't build those relationships in a year or two. I picked up some of the relationships from my dad, he's good at it. But a lot of them we built up on our own in that time.

How does it happen that entrepreneurs from Chrudim suddenly become one of the ten largest companies in this industry in Europe? Because it's not a common Czech story. It happens, but it's not common.

It certainly won't happen overnight. You have an ambition, and you just make it happen step by step. Everybody has to have a vision, a dream, where they want to take it. I'm partly fulfilling that dream now. I believe it's all about hard work. You know, we also went through through more difficult times, we haven't always been as successful as we are today. And maybe that makes us all more aware that it's not a given and that there have been worse times. I think, when you get to a certain level and you also start to learn about your competitors, European and world players, you will find that there are many things that those Czech and Slovak hands, as I say, can do much better, more efficiently and more interestingly.

Overall, it's great that we have those little hands, but it's about your brain. How would you explain to someone who has never heard of Michal Strnad or his father, and now reads about billions of euros and world business, how it all started?

Dad started it in 1995-1996, when, after the collapse of the Warsaw Pact, the countries that were gradually joining NATO began to get rid of post-Soviet and Russian equipment. And they began to rearm with Western equipment. They sold the post-Soviet equipment as unnecessary assets at almost scrap prices. We were buying it up because my dad's original business was actually scrap metal. So first the equipment was bought up, cut up, and really scrapped afterwards. But then we gradually found out that what we were buying out could actually be repaired and sold to third world countries, to Africa, to the Middle East, where there was an interest.

That's a giant leap, isn't it? Instead of selling it for scrap, saying why do that when it can go to Senegal?

We were buying more and more equipment and spare parts, and suddenly we were being approached by various traders asking why we were throwing it into the scrap heap. We could repair it and sell it to Vietnam. So, we did the first deal, then the second, then the third. At that time, we were still buying, for example, medical and gear material, so we had large warehouses of camouflage and similar goods. Then we started buying everywhere we could, not only in Europe. At one time we had more equipment in stock than the Czech and Slovak armies combined. Tanks, IFVs, Tatra trucks and other products for which we gradually found customers. We repaired them according to their wishes, modernised them and delivered them. And then later, we suddenly ran out of saleable equipment. But because we gained some experience through repairs and modernisations and we understood the technology, we started to develop it, or let's say, to improve and produce it to the state where it is today. And, of course, we made acquisitions of companies that fit into our group. All this with the aim of being able to serve the customer comprehensively, so that when we deliver a howitzer, we can also give the customer ammunition and an ammunition vehicle on a Tatra chassis.

In short, from buying scrap to someone who is able to deliver absolutely world-class equipment?

But think of it as thirty or twenty-five years of work. If I take it from 1995, that's 28 years of work up to date.

When you put it that way, from scrapping it to delivering it to the US military, it sounds crazy.

I was interviewed by American Forbes less than four years ago, and they were also absolutely horrified at what was happening in Central Europe. I'm sure we were also often in the right place at the right time.

It was a time that was full of opportunities.

One thing must be said... We built what we have today from the scratch. We did not privatise anything, the only thing we bought from the state at that time, except for the unwanted equipment – was the military repair plant in Štenberk. That was in 2013, when it went bankrupt. So we actually saved it.

Will your father be happy now when he learns that you are in the list of the richest people in the world? Not the richest, but the most successful, because money is just an outlet, a yardstick.

I'm sure he'll be pleased, I suppose. On the other hand, knowing him, he'll also have his finger raised. I'm imagining something like "I'm happy but be careful because it's very windy up there". If you know my dad, you know that it is very likely that such a parable is going to happen.

What is the dynamic and nature of your relationship with your father today?

We talk less and less about business. He does his things, I do my things, we don't meet often. Of course, when we can, we help each other out, it's the logical thing to do. But our businesses are strictly separated. I'm not saying that we don't keep each other informed and tell each other what went wrong or what went right, but it's not like we talk about it in detail. We each have our own team, we're each responsible for something. It's probably appropriate to say here that because my dad had me very early, in his twenties, we have more of a brotherly relationship than a classic father-son relationship. By the way, my brother, who is now 24 years old and works in Slovakia in our ammunition department as a sales manager, also works for me.

But we still don't fully understand the fact that a dad decided to hand the company over to his son when he was less than 50. Even in Czech business, we know the opposite stories, where the founding father doesn't even want to lend his son a pencil sharpener and holds on to the helm as long as he can...

This is definitely not our case. You see, I have a hard time proving this at the table in front of you, but ask my colleagues who hired them, who interviewed them, who makes business decisions, and how many times they've seen my dad in the company over the last ten years except when we celebrate birthdays.

And how did it happen?

He just made a decision. In 2018, my dad was still 100% owner, I was running the group. We sat down together and he's like, hey, you're running it, it's yours for real today, you're doing it, I know almost nothing about it anymore. And so, we just agreed that he'd sign the group over to me and he'd go to do his business, which he enjoys.

That's still hard to understand. The founding father didn't take any money out of it and just signed it over?

Oh, watch out, he did. He took the money because he owned Tatra as an individual, and we as CSG bought our stake in Tatra from him. It wasn't exactly a small amount of money, and Dad built his new group on it, which he owns, which he is building, and which he enjoys certainly more than the arms business. You also have to understand that my dad isn’t the international business type, because for example, he is not very well equipped with languages. So today he's doing what he enjoys. And with people he enjoys being with. I have to say, he's happy that we're successful, that we're doing well.

Emancipation between founding fathers and follower sons can be difficult.

I have to give my dad full respect here for stepping aside and saying: Hey, go ahead. You're either going to get your ass kicked or you're going to make it. And it worked.

Was there ever an option on the table for you not to continue in the family business?

My dad never pushed me into it. I wanted it more than he did - not to be direct owner, but just to be in the business. I'm the one who blew off school and went to work. Today, my dad is approached by entrepreneurs who started in the 1990s, are in their 60s, have kids, and want advice on how to pass the business on to them.

And what do you think about that?

When they see that their kids can do it, that gives them the confidence. If they see they can't do it, they'd better give it up, sell the company and distribute the money to them in some investments that will bring them annual appreciation. And goodbye. Forcing someone who doesn't want it or can't afford it is utter nonsense.

Was your dad hard on you?

Pretty much yes. Or rather, he was principled and strict. If I was running off somewhere, he'd sit me down and explain very firmly that, "Hey, do not do this.” It wasn't easy sometimes, and of course when I was smaller, it bothered me. Today I am grateful for it.

Will you be the same parent?

I will try, but of course within some limits because I grew up in a different context. We didn't have anything; I didn't even graduate from a proper college... My younger brother was in high school in Switzerland, which costs a fortune. Then he was in London for college. The overhead around it, of course, costs millions. That would have been a total stretch for us in view of the time.

What has completely surprised and shocked us today is the level of detail you know about all things. In every corner of the factory you know, this is this, this is that, we're missing gears now, we've got a problem with this. Then we're talking in the car about the brakes on a railroad carriages and again you know the detail. That's not exactly common.

I'm sure it's because, and I don't want this to sound like a cliché, that my job is also my hobby. I enjoy it so much. And of course, I'm quite hands-on, as they say. I'm visiting all the companies regularly, the big ones at least once a month, the small ones once a quarter, so that the employees can see that I'm interested in them.

So they can feel the interest of the owner...

It’s about stopping in there, talking to them and asking where I can offer help. Because sometimes they’ll tell me what they don't tell their managers. And I enjoy it. And to your question, by being primarily involved in the business and the strategy of the group, it all starts with the business. And so, I know which contracts are which, because I'm always present at the biggest ones in some way. Buy in trouble, restructure, get it into shape and eventually into profit.

--

That's the story of Tatra under the Strnad family and basically the model that the father-son entrepreneurial tandem has applied in many businesses - from scrap to Prim watches. The slogan of the Penta investment group used to be "we see opportunities where others do not", which would fit the Czechoslovak Group too. It is precisely for the strength of the opportunity, or rather for its fulfilment, why Jaroslav Strnad has been historically criticised. He was criticised for his long-term sponsorship of the campaigns of Miloš Zeman, with whom he flew on business trips and from whom he earned the Medal of Merit. He has also been criticised for allegedly supplying arms to embargoed countries or for his alliance with Russian businessman Alexei Belyaev, who has links as far afield as Vladimir Putin. Zeman is gone, there were never any sanctions for allegedly supplying arms to embargoed countries, and the partnership with Belyaev has also been non-existent for a couple of years. So, you could say that the Czechoslovak Group, headed by Michal Strnad, is looking to the future without the scars of the past, and what's more, those who used to look down on the group now see it as one of the main defence pillars of the region.

They are not only a partner of many NATO countries, including the alliance as such, as well as the Czech Republic at home, but they have also armed the Ukrainians quite extensively. Since January, however, for security reasons, they have stopped communicating about supplies to Ukraine altogether, and Michal Strnad is reluctant to talk about this topic today on-record. However, reports from last year indicate that Czechoslovak Group delivered Tatra chassis, DANA howitzers, rocket launchers, tanks, tracked combat vehicles and ammunition to Ukraine. The CSG's strategy and opportunities today are thus undeniably largely in the West, as Michal Strnad recalls during the interview.

What do you think the group should look like in a few years? Where is it heading, what will it be? And will it still be Czechoslovak Group? Because already now you have things that are not completely Czechoslovak.

Our name was chosen at a time when we were really a Czechoslovak group. Today we probably won't change the brand because we are known by it, maybe we will shorten it from Czechoslovak Group to CSG only, but we will see. We are actually talking about it internally. We have other foreign acquisitions in the pipeline and for those we are buying, our full name may be a bit confusing.

Limiting...

Exactly. But when you ask where the group should be in a few years... The group should definitely become a European leader with a clear focus on the core businesses that we do. And of course, most of our energy goes into the defence industry. We have big plans, sometimes it's more difficult to implement them. We thrive on skilled people, but there are only few of them.

Do you lack brains and hands more than money?

There is a lot of money, in quotes, or you can somehow find it if you don't have it, but we definitely lack the brains and hands to take advantage of the growth we are experiencing.

And as we asked about the perception from the outside, towards the arms, defence industry, in that sense, has there ever been a problem where you would see a skilled manager that you wanted, and he would say that he couldn't work in this industry?

It happened to us before the war. Now after last February twenty-fourth, it hasn't happened to us. On the contrary, people are coming forward and saying: We want to help, we want to work here in this industry.

So it's a complete turnaround.

Totally. The same when the banks turned around. The defence industry in the pre-Ukraine days was at such a level that some banks didn't want to finance us. Today, some of the banks themselves are coming in and offering us money.

So, the war has completely changed the perception of the defence industry by 180 degrees. And by that, as you said, you were always very much in business. Has that changed as well?

Before that, we had to be very aggressive and business experienced to get contracts. I'm not saying we don't have to be business capable today, but in the past we were really knocking on customers' doors. Today they are knocking on our door and asking us to leave them at least some capacity. For example, in artillery and tank ammunition, that's where customers are really begging us to leave them at least something for 2024 or 2025.

You see custom four to five years ahead?

Absolutely, and there are customers who offer us ten-year contracts five-plus-five, perhaps with options. The market is really pushing forward and a lot of money is going into it. Take a look at how even the goernments are increasing spending...

The share of GDP spent on defence...

Exactly. Even the Czech Republic will have two percent of GDP for defence as a law.

How does business get done in your sector? Are trade fairs the main acquisition channel?

Trade fairs are more of a presentation. The standard way is that customers, meaning ministries of defence or the army, issue tenders, selection procedures. If you want to get into them, you need to meet certain criteria, primarily you have to be certified. Then, if we talk about military vehicles, for example, they are sent for trials, where they run for six months to a year, so that you have a vehicle and a team of people with it at the customer's place all the time. They do all sorts of tests, they evaluate everything honestly, and at the end there is a summary where they determine who was the best technically, who was the best pricewise and so on. It can sometimes happen that the one who won wasn't the cheapest but had better technology. This is what happens to us in Tatrovka, for example.

But Tatra is expensive...

Tatra is the most expensive. But even though we are the most expensive, we win tenders, for example the recent big one for the Belgian army.

Are you expecting something like that, such a big tender, this year? Or something that you're looking forward to?

We are also looking forward to big tenders, for example, for the US government or the US army. There are big tenders in Morocco, there are big tenders in Indonesia, there are big tenders in India... And finally, there are also contracts for the Czech army.

And if we go back to the vision of where the group wants to be in three to five years, it logically leads us to acquisitions. Do you have anything like that in the pipeline now? I think Fiocchi surprised a lot of people.

Well, it was quite a big acquisition that really changed the whole group and the way we look at it. We're a little bit more world-wide again. I don't want to be too specific, but yes, we are looking at other acquisitions, other companies that will help us to be self-sufficient... For example, in ammunition. Just to complete the circle.

Maybe because of your lack of gunpowder?

For example. And then we're looking at two bigger acquisitions than Fiocchi, but you know how it works with acquisitions. We've been negotiating Fiocchi for almost a year to get the project done, so it's not going to happen overnight. And most importantly, until it's signed, there's no deal, there's nothing.

Is it within your capabilities to make such an acquisition?

It is, but of course it always depends on the circumstances. We can do something on our own, for something huge and global we might bring in a partner. That's open.

Can we jump to something else entirely?

Sure.

We'd love to know who Michal Strnad is. We know a few things, but we'd be interested in normal things. What does your day look like? You said this morning when we were at the airport that you were up at five...

I always get up at 5:00 or a little after 5:00 on weekdays. It sounds hard, but if you learn to do that, you don't have to sleep even on the weekend, so even on the weekend I'm usually up by six. I get up, and if time permits, I go at 6 AM or slightly after 6 AM in the morning to work out, to at least do some movement. I don't do any sports and this business is very sedentary - in the office, in meetings, on planes...

You always sit at lunches and dinners like you do now...

Yes, yes. And of course, I start early in the morning, I usually fly somewhere at 6:00 or 6:30, or I travel to different companies for board meetings or foreign meetings, or I'm in the Czech Republic in Prague, where I have meetings from morning till evening. It's really a lot. If I show you my calendars, you might be very surprised. So, from morning till night. Work, work, work, work. I'm not the administrative type, I don't even have an office, I have two meeting rooms, as you know, that I go back and forth between. My added value, and where I can help the most, is in relationships, and you can't build those without meeting in person.

Where's some free time? Some people don't know the difference.

I do. Certainly, since my wife and I had our little boy. I try to keep that at least partially on weekends, I used to not keep them at all, I was at work the whole weekend. Now, if it works out and I get home before 7 for example, I try my best to spend time with my child and my wife and be with them. Enjoy the little big pleasures, play with him, give him a bath. Just spend time with the family.

So work and family. What about hobbies?

When it works out, in the winter we go to the mountains for a weekend, skiing, maybe from Friday to Sunday, or go on holiday in the summer, if we can, for example to Croatia or Italy. And then, of course, over Christmas, between the holidays I try to keep as much distance from work as possible and take my family, even with my grandparents, somewhere, where the weather is warm.

Do you have that discipline and diligence in you since you started in the warehouses?

I do. When I started in the warehouses, my grandmother was the boss, and she was my dad's boss in the equipment warehouse. They worked there from six o’clock. We had to get up at five and go to work. There was no train running through, that's how it worked. I guess that's where I learned it and I've kept it ever since. And it's a fact that I'm generally an early bird, not a night owl.

You're mainly Strnad (Bunting).

Yeah, no doubt. (laughs) I just wanted to say that I'm not the type to stay at work until midnight. If I don't have a business dinner, I really want to see my last job at eight, nine tops. I know that after that, my focus, my energy, goes down dramatically... And it's not worth it.

What's the best thing your dad taught you?

A lot of things. I'd especially mention his business attitude of chasing business. Not playing games, telling it like it is. Honest and hard, don't mess with it. Being able to praise people for a well finished job, being able to tell them that something is wrong. To get things right. And above all, to build and develop relationships, that's what he always knew how to do.

Was he?

He was and still is a very relational, social type. He can come to an agreement with somebody, with whom I cannot. I'm maybe more structured than he is, so I can have a problem with that sometimes.

Isn't it sometimes a nuisance if you're too structured?

I'm not saying I'm too structured, I'm saying I'm more structured than him. (laughs)

Do you have any guilty pleasure at all? Because so far, we're not getting any...

I don't know if guilty, but I get pleasure from cars in general, motorsport. When I am lucky, I like to go to the track with a bunch of people. But I admit, when I think about it, I'm probably doing it wrong, and I should make more time for my hobbies. Taking a break is good, for the person and the business. A lot of people, busy people like me, often say that what isn’t on the calendar isn’t happening, and as I am not planning trips, or putting it on there, something more important than just going for a ride always creeps in. I like to hike in the mountains, I like to ski, I sometimes go to the sea too, but that's more at the request of my sweetheart.

When was the last time you went to the seaside?

Well, between the holidays at Christmas. My son was still so young that he wasn't into skiing, he's a year old, so the choice fell on the sea.

What do you enjoy most about business?

I definitely enjoy pushing things forward, I enjoy success and looking back at what we have achieved in the year, two, five or even ten years that we have been in Tatra. I like to look back and say that maybe we made a lot of mistakes, but at the end of a day, we did a great job. I have to say that I used to enjoy travelling a lot, now I enjoy it less and less because it's so time consuming. It's just how our business works. And of course, a minister from Indonesia or Vietnam is not going to come to me.

But that's a different kind of travel, isn't it? You don't get to experience much of that country.

I've been to dozens of countries, maybe 50, but as you say, I don't see much of them. I'm going to Indonesia next week. That's a 16-hour flight. I'll fly there, make the necessary arrangements and fly back the next day. I very rarely stay somewhere for longer, unless some local partner or customer prepares a program for us. But otherwise, the trips are short. I try to make long trips as short as possible on purpose, too, for the sake of not overstaying there. Because if you're there longer and you get overrun, it's awfully hard to get back. When I'm traveling for one day, I'm pretty much on Czech time.

Are you happy? Because you're successful measured by money, but what about happiness?

Happy, I must say I am, I have a healthy family. Whether the closest one or extended, thank God we have no serious illness in the family. And I'm happy professionally too, I enjoy what I do, and I'm so comfortable that if I ever stop enjoying it at some point, I know I don't have to do it. But I say, it's all about health and we'll deal with the rest because it's fun.

Can you imagine not working for the rest of your life?

I wouldn't have to, but I wouldn't be able to do it, I wouldn't know what to do. Or maybe I would, but I think I'm still young and I wouldn't enjoy it. Who knows, maybe we'll meet in five or ten years at some other interview, and I'll tell you I've got another year and I'm handing it over to the managers and I'm going to enjoy the wine or I'm going to plant vineyards. It's possible, but today I can't imagine it at all.

Now that we've touched on health, I can't help but ask - do you have any special safety requirements for your transport and life in general? Because logically, you're always a stone in someone's shoe.

Sure, we definitely have higher security, you might not quite see it here, because the important thing is that you're safe and at the same time it doesn't bother you and it's not such an invasion of your privacy. It's obviously one of the possible risks in this industry, although I think the nineties are over. That would be what the boss of Rheinmetall would have to fear for his life today, or the boss of Leonardo, the boss of Nexter, because they also supply arms to Ukraine, for example.

We have been talking all the time about how successful you are and how good you are doing. But was there a moment when things weren’t as good in the group?

We were never at a loss or broke any contracts, but there were cases, for example, when we went into a deal that was so big that we just barely made it. We took a big bite and, for example, we didn't deliver on time, so the customer slapped us with a penalty, which can be hundreds of thousands a day. Of course, that happened to us, but from today's perspective, I don't want to say outright that it was positive, but it was a lesson. Expensively paid, but it pushed us somewhere and we learned something. We had contracts where instead of making 200 million, we made 100 million. In short, you don't make money on every deal. Maybe you do, but I don't.

We don't.

There you go. And that's just the way it is.

Share